Intro

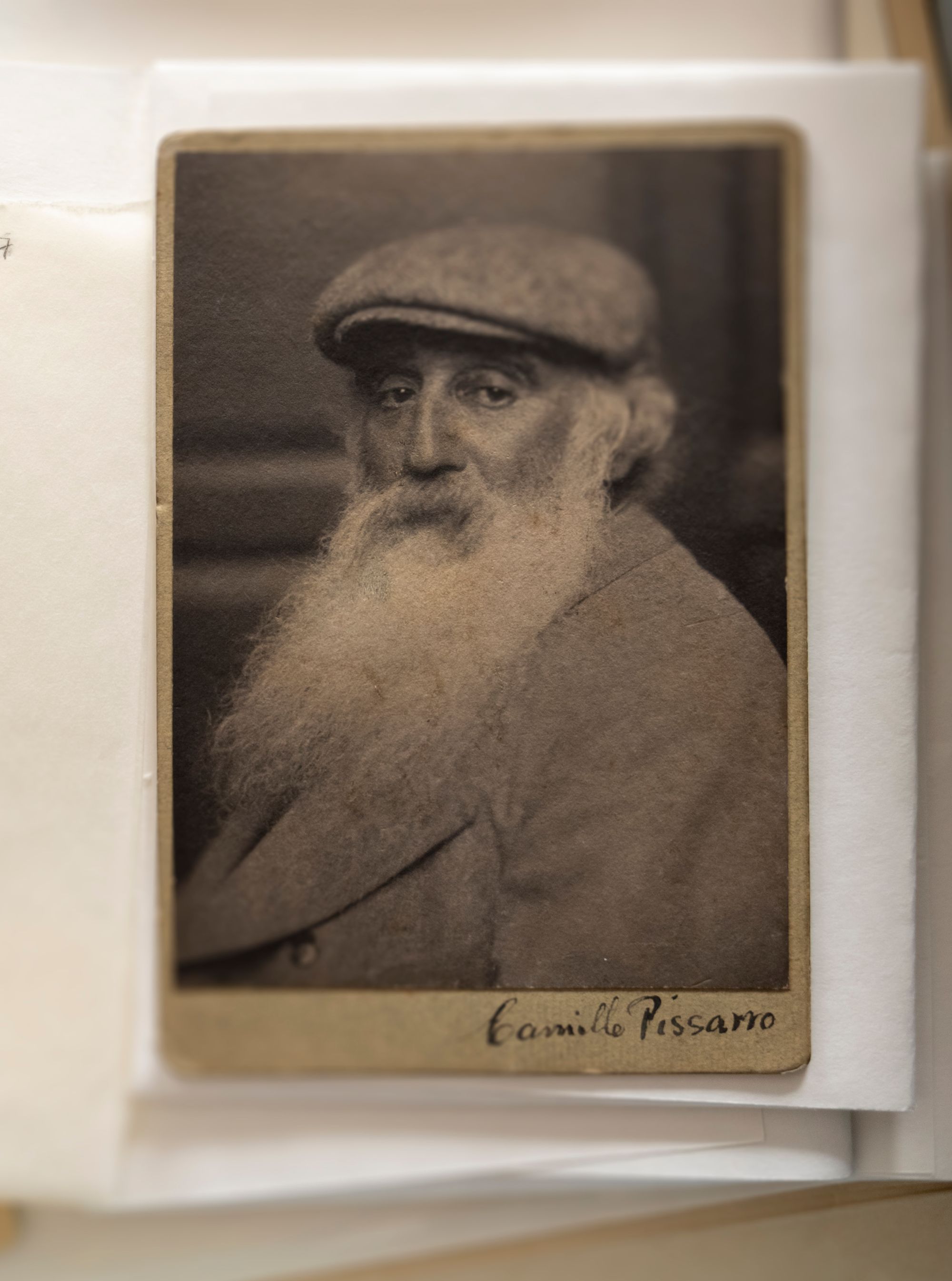

Camille Pissarro - the 'dean' of the Impressionists and the contemporary of Monet, Cezanne, Degas and Gauguin could also be called the rebel altruist and a one-off, rare genius with the ability to turn paint and his many splendored artistic experiments from the ordinary into a sensation.

That is certainly the exciting idea which is explored in an original and carefully executed new retrospective of his work, the first for twenty years, at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, Britain's oldest public museum and in a new Pissarro film by Exhibition on Screen launching in cinemas from May the 24th - which dramatises his life with a sense of intimacy, fun and twinkling passion by using the heartfelt letters, he wrote to his family, especially his son Lucien, one of five sons who would all become artists much to the despair of his wife Julie.

"Go and wallow in Pissarro's 'sensational' art on film and in Oxford's dreaming spires - it's like taking an exhilarating holiday filled with colour, hustle and bustle, shimmer and rebellion." The Luminaries Magazine.

Painting the Sensation

On the one hand, Pissarro rejected capitalism and refused to choose aspirational subjects, painting the agricultural labourer instead of the middle classes at leisure and on the other, he makes nature so alluring, sexy and iconic by painting with emotion, luminous light and colour, not realism, that the effect of looking at his painting of the women staking peas or the apple pickers is no less extraordinary than Monet's waterlilies. They are both magical pictures.

So which are the greater and more relevant paintings now?

"Camille Pissarro is unique among the Impressionists. His work rewards close and careful attention that reveals a hugely sympathetic and humane artist. Unlike his contemporaries, he never compromised for the market; he was willing to learn and experiment; but he was always devoted to painting the 'sensation'. Consequently, he is the most sincere and authentic of all the Impressionists and his influence on his own and succeeding generations of artists is impossible to quantify." Exhibition curator, Colin Harrison, the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

There is no doubt that he made life hard for himself as a political act. For most of his life, he refused to join his peers and paint according to the public or intellectual tastes of the age. Instead, he painted deceptively complex, lyrical scenes of peasants, poor farming communities and landscapes that transport the viewer to a kind of Elysium, rather than to the dirt and hard toil of peasant life.

Perhaps he is nature's greatest advocate, and his time has come as more and more people are returning to work with the land and regenerate nature and its ecosystems.

An Intimate and Enthralling Voyage in Pissarro's Life and Passions

All of this is explored with a fresh brilliance in this intimate and enthralling exhibition of his life, art, family and restless intellectual spirit - Pissarro: Father of Impressionism at The Ashmolean which makes full use of the Pissarro family archive and shows that he was a master at drawing and engraving as well as painting and that his output was spectacular. As a piece of academic scholarship, the exhibition and film seeks to redefine Pissarro's importance as the architect and artisan of the Impressionists and that is well-argued.

It follows the museum's collaborative involvement in the Kunstmuseum Pissarro retrospective in Basel last year and in David Bickerstaff's captivating film which also documents his complete rejection of his Jewish upbringing, faith and culture. Camille didn't bring his children up to be Jews either, but there are some suggestions that he experienced anti-semitic feelings from contemporaries in the art world and that he thought his early struggles and lack of success were ' a matter of faith'.

"Pissarro was a very versatile artist and a great drawer, which the public doesn't know." Claire Durand Ruel - Pissarro Expert

Both the retrospective and the film dovetail seamlessly and demand that the art lover see both. Together, they succeed in dramatising Pissarro's life and passions with the same attention to detail as in his intoxicating odes in paint as a voyage of experimentation, joy, emotion, stoicism and beguiling social anarchy. Reader, I can almost hear him say, let nature do the talking.

A Powerful Distraction - Art

On the one hand, Pissarro is the quiet rebel Impressionist and the grandmaster of them all, who nurtured talented younger artists without any sense of hierarchy and encouraged them to exhibit as a collective which would give birth to the movement of Impressionism, the most popular of all artistic movements. Without his tireless passion for his 'powerful distraction - art,' there would be no Impressionism. And yet, until the last decade of his life, he resisted the call to paint pretty, iconic subjects to charm the public and wealthy art collectors.

His Most Accomplished and Critically Admired Work

He appears to have softened his views towards the end of his career. When he was beset by eye problems, he produced some of his most accomplished works in a painterly style that would lead to critical and commercial success. Notable among these works is the magical painting of the Tuilleries in the rain and there is the most wonderful painting of the bridge crossing the Seine in Rouen, caught in the evening light with all the hustle and bustle of the world at large on the bridge contrasted with smoke from the neighbouring industry. I could sit and look at that painting for hours!

In the earlier decades, he immortalised anonymous women gleaning in the fields, the apple pickers in the late afternoon sun or the simple industry and animation of rural agriculture life and of nature herself. Today, we can fully appreciate the effect of his paintings and they appear 'sensational'. Alas, at the time, it was artistic suicide to paint peasants and people of no social standing or importance.

Driven by Art, Not Necessity

As a result, his early life was a struggle to be an artist, to be understood for his ideas and innovations and to keep a family of eight and gently ignore the bitter chastisements of his wife, Julie, which are documented in her forlorn letters to him and give the film a vivid sense of the everyday struggles and discontent in the Pissarro household. Not that Camille took any notice of his wife's complaints about the state of their finances. In fact, he seems astonished by them with the reaction of a child and declares that he had better rush home from his painterly adventures! As curator Olga Osadtschy says, "Pissarro didn't let anything get in the way of making art."

Given that Pissarro was widely liked by his artistic peers Monet, Cezanne and Berthe Morisot for his warmth, charisma and generosity of spirit, there is no suggestion that he was deliberately irresponsible towards his family. It was just that art always came first.

It is interesting to learn that Julie even had to go behind her husband's back and ask Renoir to lend her the money to buy the house they rented when it was about to be put up for sale. Renoir gave her the money and in more prosperous times it was repaid.

There is no doubt that Pissarro was a man driven by altruistic ideals of what society could be. A man compelled to make art, even though it was rejected by the powerful art salons of the day for years. He could have lived a life of comfort if he had either painted to order or continued to work as a clerk in his father's merchant firm in the Dutch West Indies, instead, he rejected his bourgeois background and ran off with his artist friend Fritz Melbe to Venezuela to paint what he pleased and party.

Both the film and the exhibition document Pissarro's youthful act of rebellion and rejection of capitalism and his drive to express his political ideas through art, which began with scenes of Gaucho on horseback racing and simple, unsentimental images of village women walking to the market. It was a taste of what was to come.

By the 1850s, Pissarro had moved to Paris, married Julie Vellay, his mother's maid, and then threw himself into a life of constant experimentation, networking with other up and coming artists and organising the first of eight Impressionist exhibitions where his work was often overlooked, derided or misunderstood in favour of the sexier subject matter of Monet's flower power lilies or Degas's prostitutes and dancers.

A Contemporary Figure

Now, more than a hundred and fifty years later, how life and art have come full circle. As Curator Colin Harrison says," Pissarro seems to be a very contemporary figure now." Pissarro recognised the importance and rhythms of nature to our very existence, and today, his pictures have a renewed power and reverence in the age of climate crisis and the destruction of nature through intensive agriculture and overdevelopment in pursuit of money.

Pissarro wields a paintbrush to depict nature as an appealing pre-industrial Eden - which looks alluring and otherworldly in the age of plastic and overconsumption. And yet, what would he think of his paintings being sold for millions when he struggled to sell most of his artworks until the very last decade of his life?

Sitting, looking at some of his serene final paintings alive with activity, colour and life, in the Ashmolean Museum's multi-faceted ode to Pissarro as an artist, genial agent provocateur and family man I feel a sense of happiness and joy. His paintings and his desire to create an impression of what he saw from a field, a hotel window or an open door were as important to him as breathing. His art captures life as pure emotion. He was also prolific. When he died in 1903 he left thousands of canvases and it is in these restless experiments that his full genius emerges.

Given his socialist principles, it is also exciting to learn that the entire Pissarro family archive was bequeathed to the Ashmolean Museum by the widow and daughter of Lucien Pissarro in 1950.

So, if you do one thing this Spring go and spend a good hour or two looking at Pissarro's life's work from his early paintings, to the intimate portraits of his son Lucien, his adored daughter Minette who died just before her ninth birthday and the revealing self-portrait of Pissarro himself shortly before his death. In the winter of his life, Camille Pissarro paints himself as a man full of humanity and vision. He looks like Gandalf. There is so much insight and pathos in those all-seeing eyes.

As a final observation, I would recommend that you see the film first, as it can only enhance your enjoyment of a slow, unhurried trip to Oxford's sylvan spires to admire a dazzling impression of the master's life in paint, life and anarchy!

Alison Jane Reid

Copyright May 2022. All Images Copyright. No reproduction.

Pissarro opens in cinemas on May the 24th 2022.

For more info visit Exhibition on Screen - Pissarro Film

or check your local cinema for details.

The Ashmolean Musem's Pissarro: Father of Impressionism is now on and runs until June the 12th 2022. For further information, visit the museum website.

This independent magazine article took more than two and half days to research, write and polish. Join ALCS and the Society of Authors and pay for journalism you love and enjoy. #paythecreators

The Luminaries Magazine is a social enterprise and it is funded by its readers, arts organisations and small, artisan businesses. Alison Jane Reid, our founder has been a leading arts and culture journalist for 25 years working on broadsheets and national newspapers in the UK, including The Times, You, The Sunday Times, ES, The Lady, Mirror Group, The Independent and Country Life. Become a paying supporter today. Subscribe here or donate below.