Sentenced revives the art, power and importance of letter writing. In this book extract about friendship and transformation, Victoria Oak and Andrew Hawke reveal how a chance visit by Victoria's daughter to the notorious Bang Kwang prison in Bangkok led to a pen-pal friendship between a London housewife and a British man sentenced to death, commuted to 50 years in jail for being caught as a drugs mule. When Andy was released and arrived back in England homeless, Victoria took him in and gave him the chance to build a new life and transform her own life through compassion, friendship and enduring adversity.

April Fool

Towards the end of March, I’m summoned to court again. The courtroom is identical to the one I was first taken to, but two floors lower down. There is a translator on hand but on this occasion no jury. My brief makes a plea of leniency, having nothing else to work with. And so it’s over in an hour or so and I’m led back to the ground level holding cell. There are not many men in it, but it’s a filthy hole, the worst aspect of which is missing the mozzie net over one of the windows. The place is crawling with a plethora of insects of all types, and the noise of them frying on the lights keeps me awake most of the night.

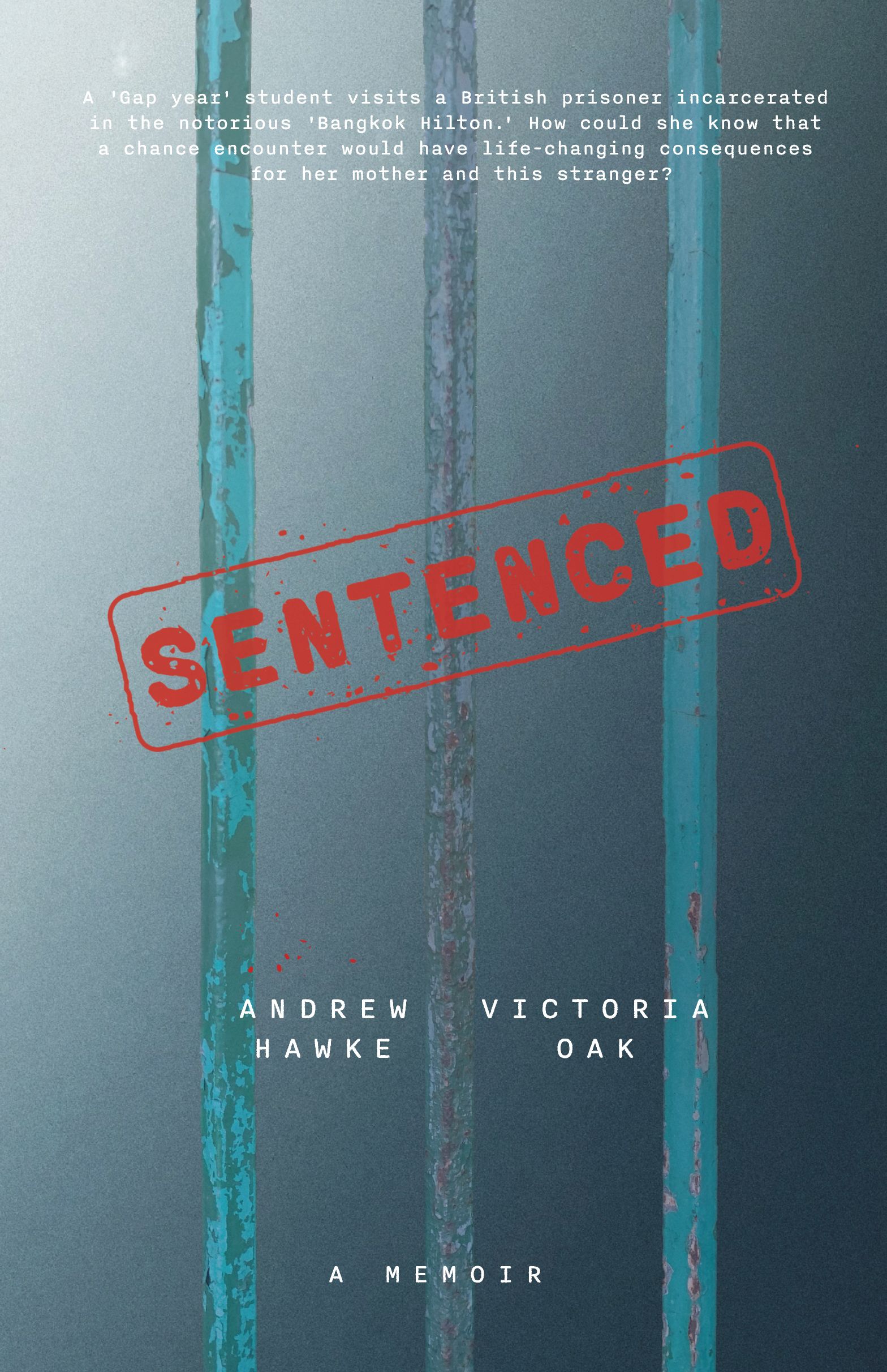

Sentenced: The Death Penalty Commuted to 50 Years

I only have to wait two days to be called back to court. This time when I enter the courtroom, there is only the interpreter, the lawyer and myself. A single judge comes in and begins to read from a sheet of paper. The lawyer’s face looks like a picture when my sentence is read. He’s surprised but pulls himself together enough to assume a look of satisfaction at a job well done. The judge repeats, in halting English for my benefit, my prison term: “Fifty years”.

The penalty is death cut to fifty years, I assume for not wasting the court’s time with a not guilty plea. All I feel is a mild surprise, not exactly elation. It is after all a life sentence. I’d had three months to adjust to the enormity of the sentence which, I admit had shocked me when I first heard of it at the time of my arrest.

Back at the prison, I’m being congratulated on my ‘good fortune’ by screws and prisoners alike. It is the next bit I’m not looking forward to. The prison has a rule that anyone who is sentenced to more than 20 years, has his chain attached to a brass rail in the cell when everyone is locked in for the night. This leaves the newly sentenced desperado just about able to piss in the toilet facility but shit-out-of-luck when it comes to taking a dump. I wonder how long I’ll have to put up with this nonsense.

The answer turns out to be just one night. The next morning I’m told to get myself together by 10.30 am, as I am off to Bang Kwang. I pack my stuff, and Nepali Andre reminds me that the bulk of my belongings are still in ‘storage’, and not to forget about them. I thank him and give him all the food in my lockers; only the cigarettes are coming with me. A short while later, I’m ushered out, after brief farewells with the guys I’ve lived with for three and a half months. I’ve learned the ropes here but now I’ll have to do it all over again in what is perhaps the most infamous penal institution in Thailand. I settle in the back seat for the drive upriver to Bang Kwang prison.

Bang Kwang - Thailand's Male Prison

The main gate slams shut behind me. The lone screw from Bambat Remand gaol follows me. Somehow I have managed to get him to carry half my stuff, a major achievement and minor miracle since screws normally carry nothing except a little light paperwork or a hardwood club. I then emerge through the inner steel doors of the gatehouse to see a long tree-lined avenue with the visit areas on either side and the entrance to the prison proper at the end. Atop sits a high tower with all sorts of aerials and speakers on it from which vantage all parts of the nick are visible.

Through another gate and round a corner to a workshop and the reason for this screw’s continued presence becomes immediately apparent. A widget with a long lever lies next to a big chest full of lengths of elephant chain. A trusty indicates that I put my shackled ankles up on the block. He then pries apart the hoops around them. I stand up as my chains are handed to my escort, but I’m only unchained for the time it takes to pick out new ones before I’m clapped in irons again. (7)

Finally, I come to the double gates set in a crenellated blockhouse; the entrance to the compound of Block Six. I recognise the Thai numeral; it’s almost a mirror image of the Western one.

A Scene Straight Out of the Film Apocalypse Now

The last steel door swings open to space, green, and lots of people. An open-sided structure, easily large enough to park two or three old DC3 ‘Dakota’ aircraft, is on my left. A very long path, flanked on the right by a riot of greenery under which are tiled concrete tables and benches, is to my right. This place is much bigger than Bambat, and though more populated, seems less congested. I can smell dried chillies being crushed, so strong I am almost choking. Chemical fumes are wafting from a local factory which I later find out makes balloons. There is a constant hum of noise, machinery from the factories, numerous fans, the constant sound of chatter, mostly Thai and Chinese, with a smattering of French and English, louder than the rest of the Nigerian contingent. And as I try to get a handle on this cacophony of sound, a flight of military helicopters appears overhead and in my head, I hear ‘The Flight of the Valkyries’. It's straight out of Apocalypse Now.

New faces, new circumstances. A crash course on the ins and outs, the do’s and don’ts, is in order. It has long been the last word in penal servitude amongst Thai convicts: the only legal place of execution in the country. By long custom and practice, all convicts within the multiple walls have at least thirty years left to serve and if, after a few years, their remaining sentence stands below thirty years, they can be transferred. If this did not happen, the place would be even more ridiculously overcrowded than it already is, more than six thousand men being held here. In the future, I will look back fondly on the days when there were ‘only’ nine hundred and sixty in our block, but for now, it seems a huge number.

The Swede with a Heroin Habit

Only a handful of the men are ‘farang’ or European in origin. One such, with a crewcut of blonde hair, detaches himself from the curious throng of prisoners. It’s Johan, a Swede whom I briefly met as I arrived at Bambat, he being then freshly sentenced and due to be shipped here the next day. He greets me with, “Welcome to Hell” but grins as he says it. He starts to talk nineteen to the dozen, and I can hardly get a word in edgeways. He is acting as if we were bosom buddies, and while I am happy to have an English speaker as a tour guide, something seems off. Sure enough, within minutes, he’s asking if I’ve brought any money with me. I tell him that the bulk of my funds are either with the consulate or now in the process of being credited to my Bang Kwang prison account, but that I’ve managed to slip a small amount of cash through. He immediately asks if he can borrow 1,500 baht, about £27 at the time. I say that I’ll think about it, but inwardly I’m sighing.

There are NO good reasons to be trying to borrow cash from a newly arrived prisoner. I can expect to get credit because all here know that it takes time, about three weeks, to process money transfers from one prison to another. For Johan to be trying to tap me before I’ve even met any of the other ‘farangs’ in the block can only mean that he is already in debt up to his eyeballs with everyone else. Such indeed proves to be the case. Johan’s bonhomie is an act. He was an amphetamine user, or abuser when a free man. Now he has decided that he’s a victim, that everything is hopeless, and he has swapped his drug of choice for a heroin habit(8).

Hot Dogs, Eggs, Noodles and Coffee

I meet some foreign or more colloquially ‘farang’ prisoners, tucked away under a long hangar with a low corrugated metal roof. Around them are aisles of lockers made of concrete. An empty one is immediately found for me, a snip at 400 baht, no payment required until my cash comes through. Dieter, a six-foot, shaven-headed thirty-something German, and Hans, a moustachioed five foot six, sixtyish Canadian citizen, stack my stuff into my new locker. A tall Burmese (a Karen tribesman I think) who goes by the name of Ken, then rustles up some ‘maa-maa’ (or instant noodles), chopping up a few hot dogs, breaking a few eggs and adding these in. A bowl of this, along with coffee, sets me up nicely, and Dieter makes me a couple of peanut butter sandwiches to take up to the room. An ice-cold Pepsi and a bottle of water for the 15-hour lock-up completes the preparations – a ‘boy’ has already put my bedroll, painstakingly hauled from the last prison, by the gates of the cell block itself.

Twenty Prisoners to One Cell

I am assigned to Room 28, on the upper floor of the two-storey block. The lighting is dim. The barred but unglazed window is above eye-level, and the sky is blocked by overhanging eaves. The bottom third of the walls are red-brown gloss and the rest is extremely worn green. It’s a rectangular space about 24ft long and 13ft wide. There is a raised, tiled cubicle in the far corner that is the extent of the ‘facilities.’ Not a stick of furniture on the floor, only the bedrolls of the twenty prisoners already in the cell. A TV in a bracket, clipped over the bars that separate the front of the cell from the corridor, completes the description of the room.

The Thai National Lottery Draw

It is soon clear that not one of the twenty men squeezed in here speak English. I’m put under the window, opposite the toilet cubicle. An oil drum of spare water, filled during the day, lies in-between me and it. A smiling Thai helps me squeeze my bedroll in, the cell door is slammed shut and padlocked, and the headcount starts. I’m number 12: ‘sib-song’ in Thai. The TV has been on since before the door was locked (though muted during the headcount) and, after the screw disappears with his clipboard, the volume is turned up again. It’s the first of the month, so at 4 pm the twice-monthly Thai National Lottery draw is being broadcast. I see that several of the men in the cell have bits of paper in their hands and are groaning, nodding, or smiling as the numbers are drawn. The old cliché of gambling-mad Asians seems confirmed.

Peanut Butter Sandwiches and Pepsi

As the natural light fades, the interior lights feel brighter. Again, they are never switched off. This is principally because the guards don’t patrol the insides of the cellblocks at night and they want to see the windows backlit to expose any would-be escape artist sawing through the bars, something that had happened a year or two before. Even looking through those high windows was technically forbidden. I eat my peanut butter sandwiches, washed down with Pepsi. As the hubbub subsides, I snuggle down into my bedroll and am asleep in minutes. So ends my first day in Bang Kwang.

Extract by Victoria Oak

2011

Back in 2008, taking Nick aside, I told him that if things hadn’t improved between us by the time William finished school, we should call it a day.

Now, three years later, it was the very day of our youngest son’s Leavers Ball, and Nick and I were attending. As Pam, my hairdresser was doing my hair, I confessed to her that I felt my life had to change, but that I had no idea how to go about it. She suggested I meet her Austrian friend Isabella, a spiritual healer who, she said, would give me, “a sense of my place in the world”.

Little did I know on our first meeting, a week later, what a powerhouse Isabella would be. I rang the bell of an elegant, early Victorian house and a smiling blonde vision answered the door. I swear she was glowing from inside.

“You have asthma,” she said, as she lead me to a pure white bedroom adorned with candles, incense and feathers.

“I take on the person I am seeing a few minutes before they arrive, and I have been struggling to breathe.”

She then sat us both in chairs facing each other. She stared unblinking at me with this beatific smile. Five minutes passed. Ten minutes passed. Gradually I stopped worrying about paying for silence and decided to use the time and this beautiful room of peace, to pray. Isabella suddenly pulled her chair towards me, looked deep into my eyes and, still smiling, said, “Your marriage is over. Did you hear me? Your marriage is over.”

After a long silence, the words that came out of my mouth were, “How sad.”

Isabella didn’t alter her expression. She then connected to my deceased grandfather who had been a Rear Admiral in the Second World War.

“Your grandfather has come forward. He is saying ‘chin up girl, head up girl.’ He is proud of you. He loves you like his own daughter. He is smoothing the path in front of you. He is at his most powerful, in his fifties, in a suit with a waistcoat. He has taken out his fob watch and it reads three minutes to midnight. He is showing me a ship under sail and passengers boarding with their luggage. He says that, if you don’t hurry, you are going to miss the boat”.

She then asked, “What is it you want to do?”

“I don’t know?” I replied.

“What is it you want to do?”

At the third time of asking, I was annoyed and without thinking I blurted out, “The GR20, The Road to Santiago and Tibet.”

She beamed, saying, “Your grandfather is nodding. He says you’ve understood and he’s putting away his watch.”

More silence, then she asked, “What does Albert mean to you?”

“I know someone in IT called Albert.”

She frowned impatiently, “no, no! What does Albert mean to YOU?”

“Well,” I replied, “Albert was the loving and faithful husband of Queen Victoria. Their love was legendary. They had nine children but sadly he died young.”

She beamed again. “Well my dear, you are going to meet your Albert and he will not die young.”

Another pause and then she said, “Your Grandfather says you are going to soar.”

She took my business card, dismissed it and designed another one. She told me that I had a gift for creating healing spaces, that I was all about balance and harmony.

The session was over, I said goodbye and realized I had to take responsibility for my life. My children were now adults; they didn’t need me for survival. I had used them as an excuse to sleepwalk through life. When I got back, I began from that moment to organise the GR20 and the Road to Santiago. Tibet would have to wait.

Vicky to Andy, 8th Letter 11 October 2011

Dear Andy

I am sorry not to have got in touch before. I think of you often, talk about you a lot, pray for you and hope you pray for me. Still, a letter counts for a lot. I love getting your letters. Anyway, William (my youngest) has finished school, so after 22-years, no more fetching, carrying, doing homework etc. I set myself to do three things (GR20, Road to Santiago and Tibet) to mark that event:-

The GR20

This is the toughest trek in Europe, beginning on the northern coast of Corsica and ending in the south. I went with Gail, a Yorkshire ex-air hostess and fitness coach. We were each carrying 7–9 kg on our backs. You follow red and white stripes of paint daubed on rocks and trees every thirty to forty metres. You walk seven to nine hours a day, arriving at a refuge that provides basic food (carrots, potatoes, pasta). We soon realised that it was better... hiring a two-man tent than staying in the refuge, sleeping side by side with 25 others and fleas jumping around the floor. We would be in bed by 8.30 pm and would have left by 7.30 am the next morning.

The scenery is rugged and absolutely breathtaking.

At two stages there was a hotel with HOT WATER!! Had a humorous moment on day one when I went into the kitchen of the refuge to ask if they had any cheese for the pasta. Was given a look as if to say, what planet are you on?

I never had a superficial conversation or met a superficial person. Everyone was fit and searching for answers. A doctor in his 60s, Joseph, told me that (35 years earlier) he had found his beloved three-year-old son dead in a nearby stream when he had meant to be babysitting. Everyone had forgiven him but he hadn’t forgiven himself. I may have helped him(42) because the next day, he came to me and said thank you, that I had given him some pieces of the puzzle. He seemed lighter, sprightlier, so I told him that the next stream, pond, mountain-lake he came to, to jump in without a stitch on, nothing less would do. He had avoided water ever since that tragic accident, but now he laughed and said he would do it. He said that when God made me, he had thrown away the mould. I’ll take that as a compliment!

Emma has given me a book co-written by the Dalai Lama and a psychiatrist, called ‘The Art of Happiness’. Apparently, Happiness is a mental discipline, so every night I am trying to make my last thought happy and the first thought as I wake happy and stretch that out as long as possible. You are not going to believe it. For the last two weeks that I’ve been doing this, I have slept through the night, every night. I no longer obsess about Nick and what women he may or may not have slept with. I am now focused on my next goal. That is; walking for six weeks alone over the Pyrenees to Santiago de Compostela. I know I can survive with very little to eat during the day and I have never been happier or felt freer than those nine days on the GR20. Talking of which, we finished the hardest part but still have six more days to go, which we are doing at the same time next year with a growing band of followers.

Another girl wants to do the road to Santiago with me but I think I want to be alone for that walk, to meet people along the way and go at my own pace.

Extracted from Sentenced by Victoria Oak and Andy Hawke, available from all good book shops including Foyles and Waterstones and Amazon. Price £10.

Follow The Luminaries Magazine, Literally Pr and Author Victoria Oak on Twitter

Twitter The Luminaries Magazine

Twitter Literally Pr

Twitter Victoria Oak